Oyster Mushroom Bucket Troubleshooting: Long Stems, Green Mold, No Pins

Share

Skinny mushroom stems mean your project needs more fresh air (CO₂ build-up), while green spots mean mold has moved in. If your family's mushroom bucket isn't producing any pins at all, the humidity is probably too low. The good news? All three problems have straightforward fixes, and understanding what went wrong is half the fun of learning.

Quick answers (so you can fix it fast):

- Long, skinny stems + tiny caps: too much CO₂ = not enough fresh air exchange

- Green fuzzy patches: Trichoderma (green mold) contamination

- No pins at all: almost always low humidity (sometimes too warm or too still)

Growing oyster mushrooms with kids is one of the best winter indoor projects for families in cold climates. But even the most carefully prepared 5-gallon bucket can run into trouble. When your little scientists come running to report that something looks "weird," it's time to put on your detective hat and investigate.

Let's walk through the three most common oyster mushroom bucket problems, and exactly how to solve them.

Why Do My Oyster Mushrooms Have Long, Skinny Stems?

Picture this: your mushrooms are growing, but they look like pale, spindly fingers reaching desperately upward. The caps are tiny, and the stems are way too long. Your Junior Scientist asks, "Did we grow alien mushrooms?"

The diagnosis: Your bucket is suffocating. Long stems with small caps mean there's too much carbon dioxide (CO₂) trapped around your mushrooms.

Here's the science your kids will love: Mushrooms "breathe" differently than we do. They release CO₂ just like we do when we exhale, but unlike us, they don't have lungs to push that stale air away. When CO₂ builds up around the bucket (above 1,200 parts per million), the mushrooms panic. They stretch their stems longer and longer, desperately searching for fresh air. It's like being stuck in a stuffy room and standing on your tiptoes to reach the window.

The fix:

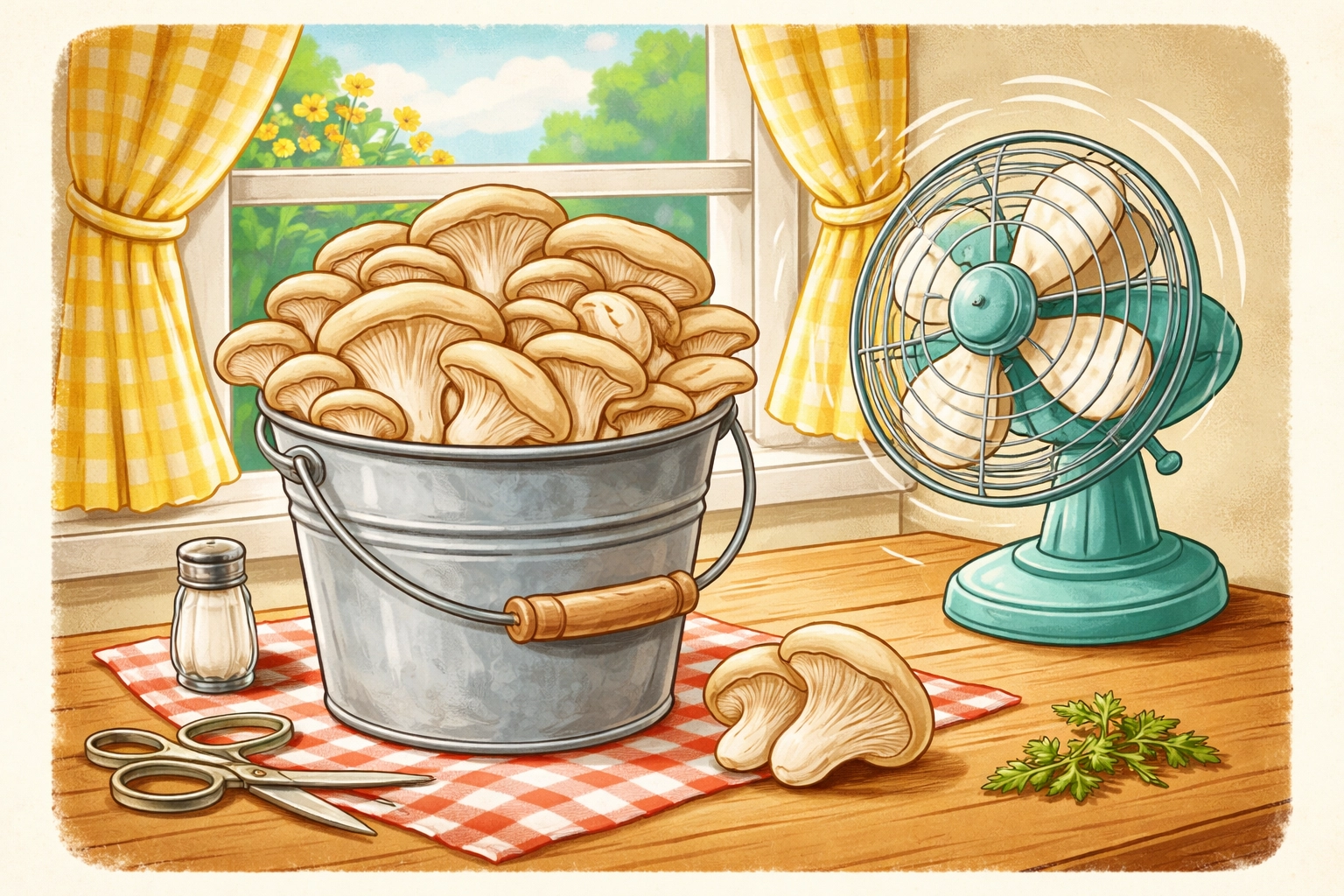

-

Add a small fan nearby. You don't need hurricane-force winds, just gentle air movement to carry the CO₂ away. A small desk fan pointed near (not directly at) the bucket works perfectly.

-

Exchange the air in your growing space. Open a window for a few minutes, crack a door, or set a timer to remind yourself to air out the room every few hours. The goal is to swap all the air in the room at least every 10 minutes during active growing.

-

Check your light levels. Sometimes long stems also mean the mushrooms are searching for light. Oyster mushrooms don't need much, household LED or fluorescent lighting works fine, but they do need some. Aim for about 18 hours of light and 6 hours of darkness.

-

Harvest and reset. If your current flush already has long stems, twist the entire cluster off at the base (this is a great job for kids!). Move the bucket to a better-ventilated spot, and the next flush should improve.

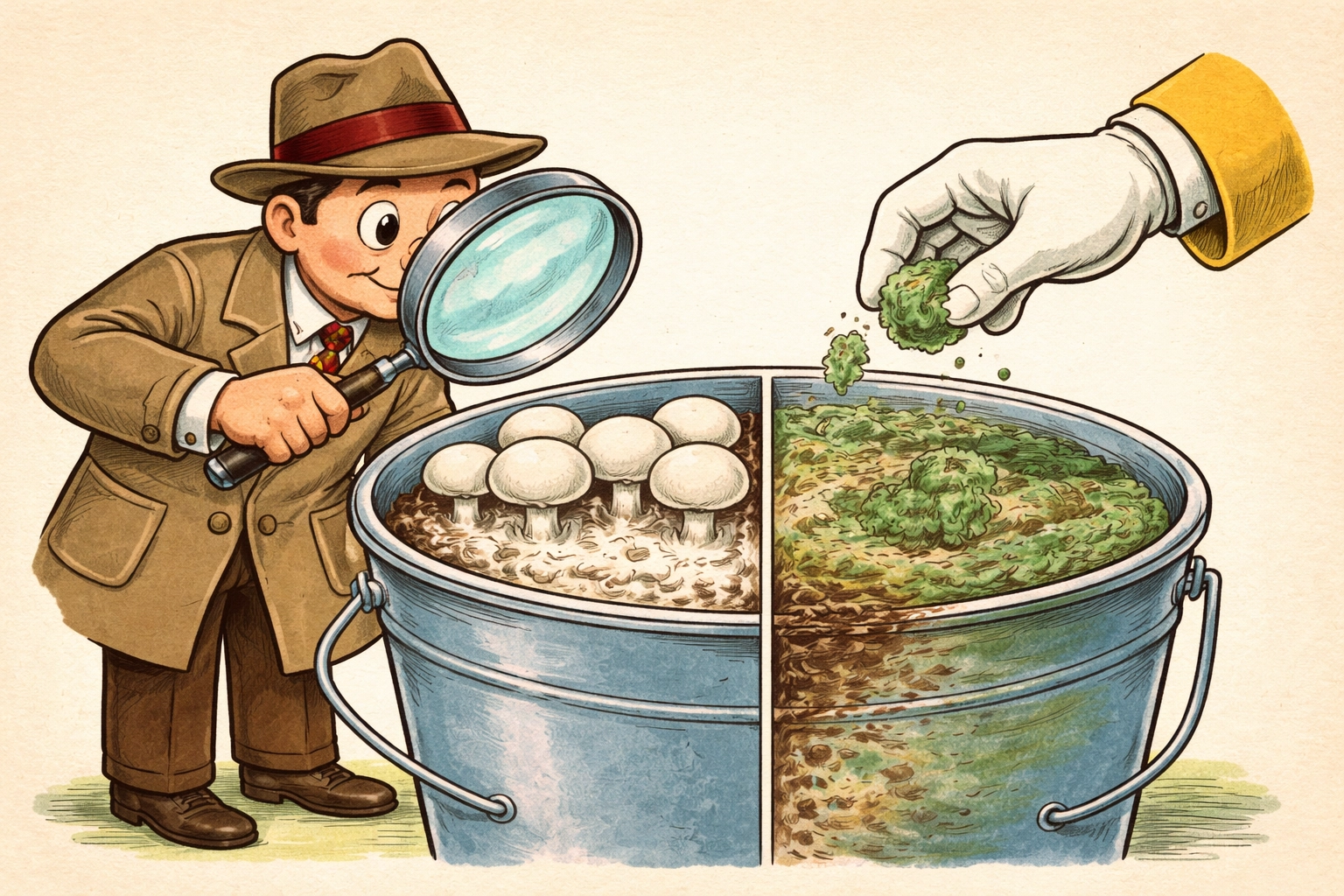

What Does Green Mold on My Mushroom Bucket Mean?

Green mold is the villain of the mushroom world. If you spot fuzzy green patches on your substrate, you've got a contamination problem, most likely from a fungus called Trichoderma.

The diagnosis: A rival fungus has moved into your bucket and is competing with your oyster mushrooms for food and space. Trichoderma is extremely common in the environment, and it thrives when conditions get too dry or when hygiene practices slip.

Why it happens:

- The substrate wasn't pasteurized thoroughly enough

- Someone touched the substrate without washing their hands

- The bucket was left open too long, allowing airborne spores to settle

- The substrate dried out (Trichoderma actually prefers dry conditions)

The fix:

-

Assess the damage. If the green mold covers just a small spot, you can try gently scooping it out with a clean spoon. Don't dig too deep, just remove the visible contamination.

-

Improve moisture. Make sure your substrate maintains at least 50% moisture content. Mist the holes regularly and keep the bucket in a humid location.

-

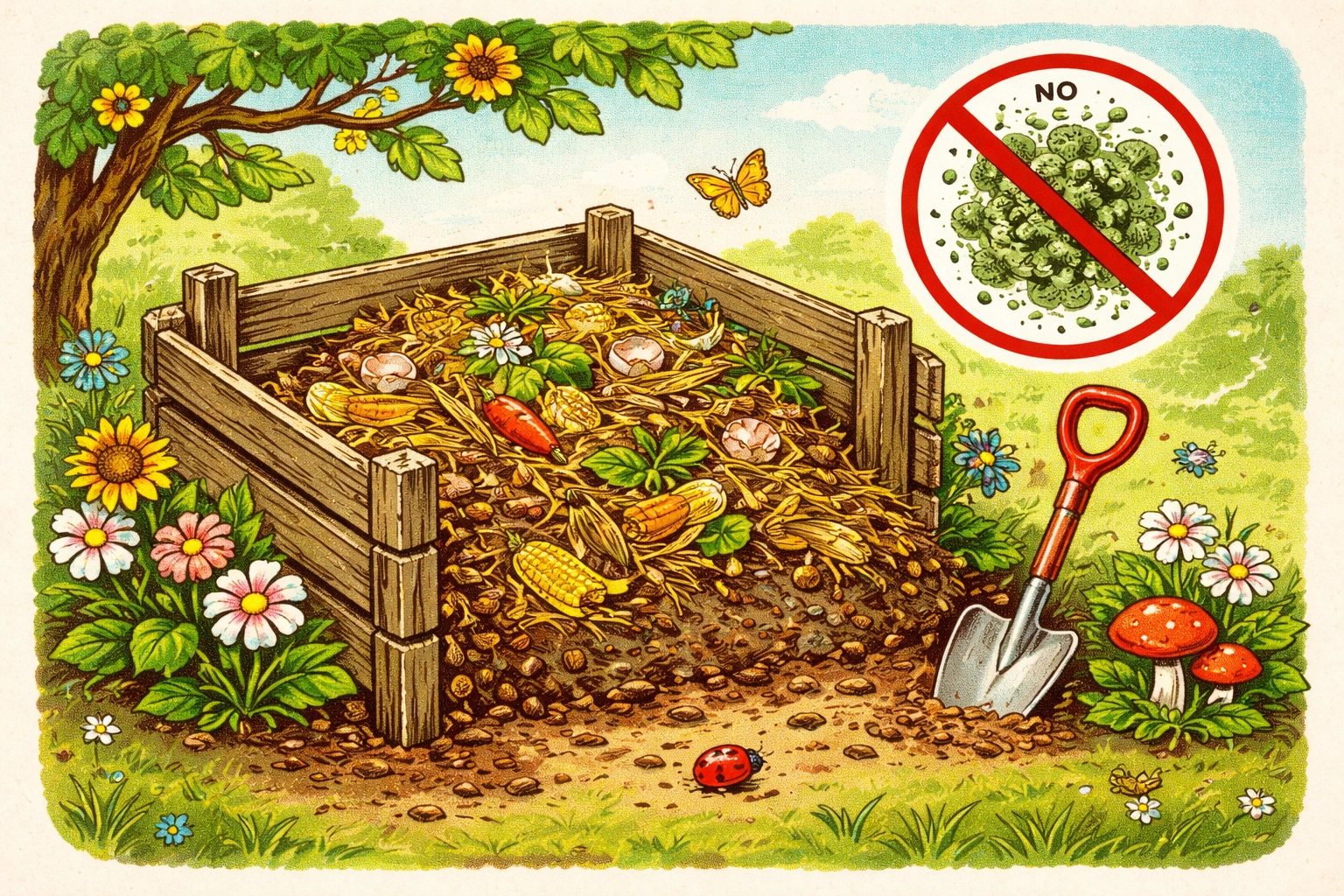

Quarantine or compost. If the green mold spreads rapidly or covers more than about 20% of your visible substrate, it's time to call it. The mushrooms will never win this battle. Compost the contents (Trichoderma is actually great for outdoor compost piles) and start fresh.

-

Learn for next time. Talk with your kids about what might have gone wrong. Did we wash our hands? Did we leave the bucket open too long? This is real science, sometimes experiments fail, and the learning happens in figuring out why.

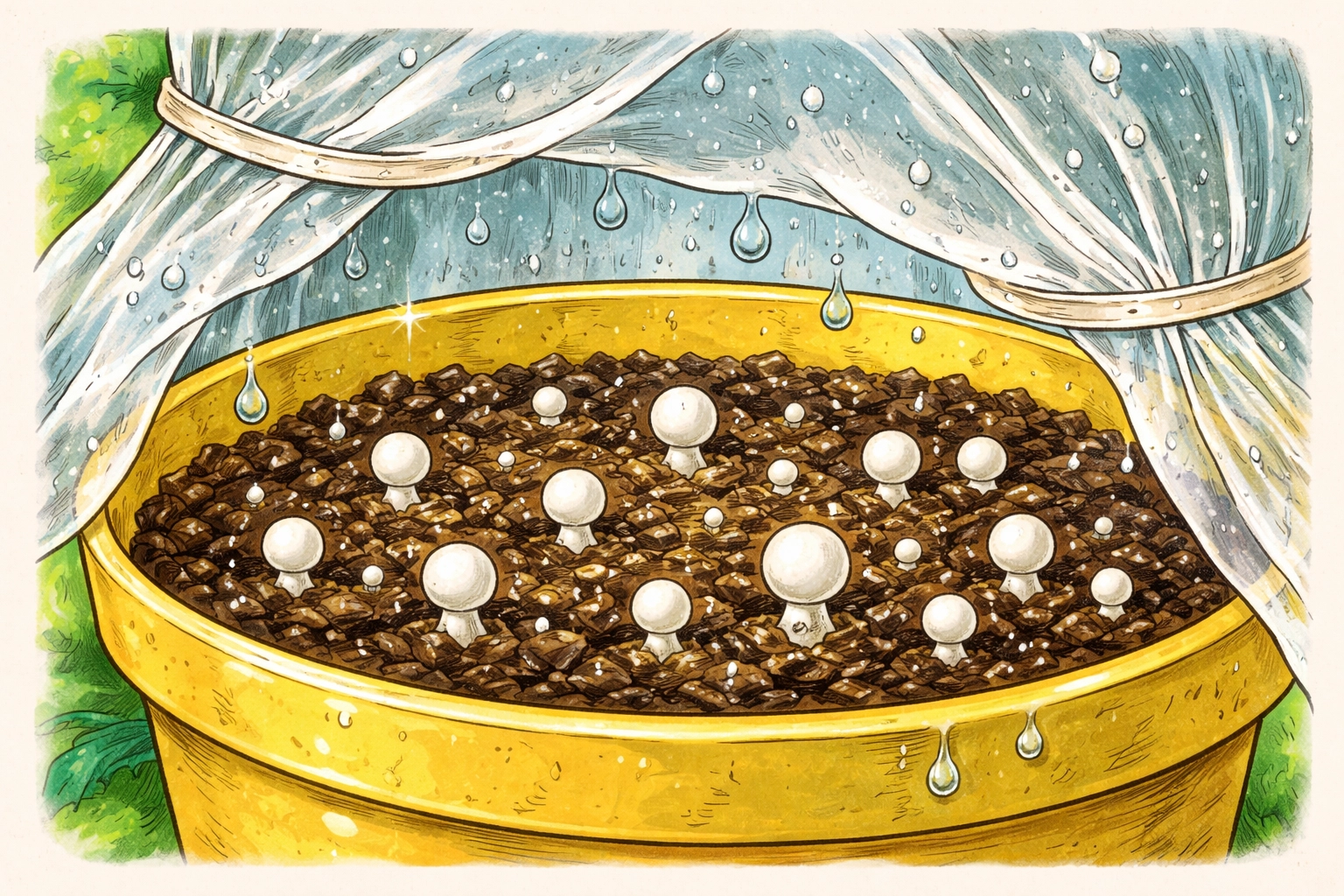

Why Isn't My Mushroom Bucket Producing Any Pins?

You've waited patiently. You've checked the bucket every day. Your kids have pressed their noses against the holes looking for signs of life. But... nothing. No tiny white bumps. No baby mushrooms. Just straw staring back at you.

The diagnosis: Your bucket probably isn't humid enough, though temperature and air circulation can also be factors.

Pin formation, those first tiny mushroom bumps, requires very specific conditions. Oyster mushrooms need:

- High humidity (this is the #1 culprit for missing pins)

- Temperatures in the mid-60s°F (62-68°F is ideal)

- Fresh air exchange (yes, this matters for pinning too)

- A trigger (the temperature drop when you moved the bucket to its fruiting location)

The fix:

-

Mist more often. This is the most common beginner mistake. Mist the holes and the area around the bucket 2-3 times per day. The substrate should never dry out, and the air around the bucket should feel noticeably humid.

-

Create a humidity tent. Drape a clear plastic bag loosely over the bucket (don't seal it, you still need air exchange). This traps moisture while still allowing some airflow.

-

Check your location. Is the bucket in a drafty spot? Near a heating vent? Wind and dry heat will evaporate moisture faster than you can mist. Move the bucket to a calmer, shadier location.

-

Verify temperature. If your growing space is warmer than 70°F, pinning may stall. Basements and garages often provide the cool temperatures oyster mushrooms prefer.

-

Be patient. Depending on your spawn, it can take 2-4 weeks after full colonization before pins appear. If everything looks healthy (white mycelium, no contamination, good moisture), sometimes the answer is simply: wait.

When Should You Compost a Failed Bucket?

Not every bucket succeeds, and that's okay. Here's when to call it:

- Heavy green, black, or pink mold covering large portions of the substrate

- Foul smell (healthy mycelium smells earthy and pleasant; contamination often smells sour or rotten)

- No activity after 6+ weeks despite good conditions

- Multiple flushes with severe problems that don't improve

Composting a failed bucket isn't defeat, it's data. Your family learned something, and that substrate will still benefit your outdoor garden.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to grow oyster mushrooms in a bucket?

From inoculation to first harvest, expect 4-8 weeks. The colonization phase (mycelium spreading through the substrate) takes 2-4 weeks, and pinning to harvest takes another 1-2 weeks.

Is a 5-gallon mushroom bucket safe to keep in a bedroom or basement?

Yes, with good ventilation. Mushrooms release spores when mature, so harvesting before the caps flatten fully reduces spore load. People with mold allergies or respiratory sensitivities should keep buckets in well-ventilated spaces rather than sleeping areas.

Can you save a contaminated bucket?

Small contamination spots can sometimes be removed. Large contamination means starting over. When in doubt, compost it out.

Why do my mushrooms look pale?

Pale caps usually mean insufficient light. Add a household LED or fluorescent light source with a blue spectrum (around 6500k) for better color development.

Tierney Family Farms Disclaimer

Mushroom growing is wonderfully educational, but please remember: only eat mushrooms you've grown from verified spawn sources. Never eat wild mushrooms unless identified by an expert. If anyone in your family has mold allergies or respiratory conditions, consult your doctor before starting an indoor mushroom project. When in doubt, throw it out: composting a questionable bucket is always the safe choice. Happy growing!

Ready to start your mushroom adventure? Check out our guide to Growing Vertical Mushrooms: An Indoor Fungi Adventure for the complete bucket setup walkthrough.

References

- Lin, R. et al. “Responses of the Mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus under Different CO₂ Concentration by Comparative Proteomic Analyses.” Journal of Fungi (2022). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9321156/

- Hatvani, L. et al. “Green Mold Diseases of Agaricus and Pleurotus spp. Are Caused by Related but Phylogenetically Different Trichoderma Species.” Phytopathology (2007). https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PHYTO-97-4-0532

- Colavolpe, M.B. et al. “Efficiency of treatments for controlling Trichoderma spp during spawning in cultivation of Pleurotus spp.” Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2014). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4323299/

- Wiesnerová, L. et al. “Effect of different water contents in the substrate on cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus.” Folia Horticulturae (2023). https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/fhort-2023-0002

- “Hypersensitivity pneumonitis associated with mushroom cultivation.” (2022). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9841544/