Instant Ice: The Science of Supercooling and Nucleation

Share

At-a-Glance Experiment Overview

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Mess Level | 2/5 (minor water spills) |

| Total Time | 2–3 hours (mostly waiting in freezer) |

| Estimated Cost | $2–$5 |

| Safety Gear | None required |

| Adult Help Needed | Monitoring freezer time, pouring water over ice |

| Best For | Middle to older kids |

| Core Science | Nucleation and supercooling |

What Is Instant Ice and How Does It Work?

Instant ice happens when you cool purified water below its normal freezing point, without it actually freezing. This strange state is called supercooling. The water stays liquid until something triggers it to freeze all at once. That trigger is called nucleation, the moment when a tiny ice crystal forms and sets off a chain reaction that freezes the entire bottle in seconds.

Under normal conditions, water freezes at 32°F (0°C). But when water is extremely pure and sits undisturbed in a smooth container, it can chill well below freezing and stay liquid. The secret? Ice needs a place to start forming, a speck of dust, a scratch on the bottle, or some other tiny imperfection. Without that starting point, the water just keeps getting colder and colder, waiting for its cue to freeze.

When you finally introduce an ice cube or give the bottle a firm tap, you provide that nucleation site. Boom, instant ice.

The Science Behind Supercooling

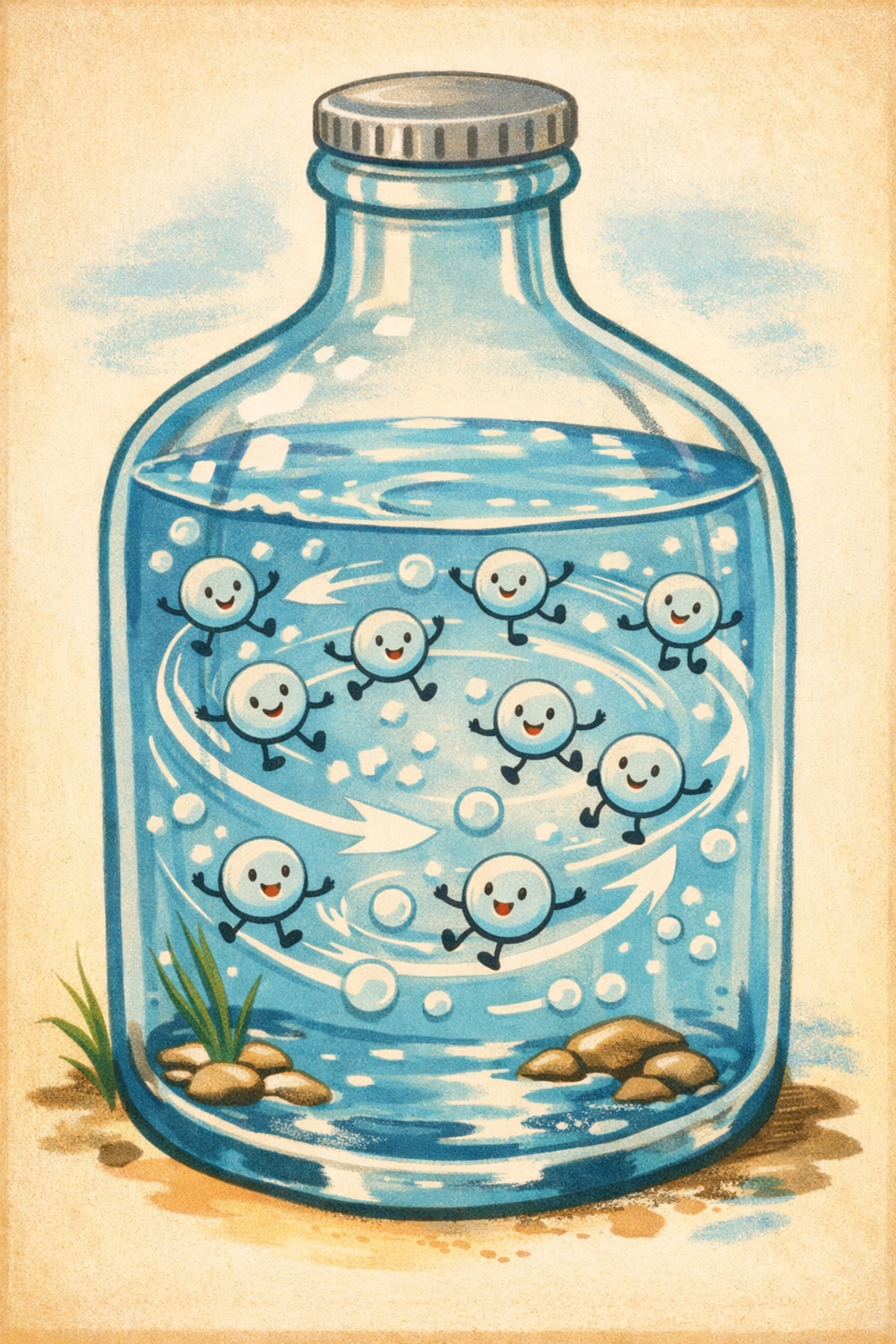

Water molecules are constantly moving, even when they're cold. To freeze into ice, those molecules need to slow down and lock into a crystal structure. But forming that very first crystal takes energy and the right conditions. Scientists call this moment nucleation.

In most tap water, there are plenty of nucleation sites, tiny particles, mineral deposits, or microscopic scratches inside the container. These give water molecules a surface to cling to, and ice crystals start forming right at 32°F.

But purified or distilled water is different. It has fewer impurities. And if you use a smooth, clean bottle, there's nothing for the ice to "grab onto." So the water just keeps cooling past its freezing point, sometimes dropping to 20°F or even lower, without turning solid. This is supercooling in action.

The moment you add a nucleation site, like an ice cube or a physical disturbance, the supercooled water molecules snap into crystal formation. One crystal leads to another, and another, cascading through the entire liquid almost instantly. It looks like magic, but it's just physics catching up.

Why Does This Matter in the Real World?

Supercooling isn't just a cool party trick. It explains some pretty important natural phenomena:

- Clouds and Rain: Water droplets in clouds often stay liquid even when temperatures drop well below freezing. Without dust or other particles to serve as nucleation sites, the droplets remain supercooled until conditions change.

- Icy Roads: Salt on winter roads works by lowering water's freezing point and interfering with the way water molecules bond together. This prevents ice from forming at typical winter temperatures.

- Freezing Fog: In extremely cold conditions, supercooled fog droplets can instantly freeze on contact with solid surfaces, creating a thin layer of ice called rime.

Understanding supercooling and nucleation helps meteorologists predict weather patterns and engineers design better de-icing solutions.

Materials You'll Need

Here's what you need to set up your instant ice experiment:

- Unopened bottles of purified or distilled water (2–4 bottles work well; avoid tap water)

- A household freezer with adjustable temperature settings

- A few regular ice cubes

- A shallow bowl or tray (to catch spills and hold your ice cube)

- A thermometer (optional but helpful for monitoring)

- A timer or clock

Why purified water? Tap water contains minerals and particles that act as nucleation sites, so it freezes at 32°F like normal. Purified or distilled water has fewer impurities, making supercooling possible.

Step-by-Step Instructions

Step 1: Prep Your Bottles

Place 2–4 unopened bottles of purified water in your freezer. Make sure they're standing upright and not touching each other or the freezer walls. You want them to chill evenly and stay as undisturbed as possible.

Adult tip: Set your freezer to its coldest setting if you can. The goal is to get the water as cold as possible without it freezing.

Step 2: Start the Timer

Set a timer for 2 hours. This gives the water enough time to supercool, but not so long that it actually freezes. Freezer temperatures and bottle sizes vary, so 2 hours is a good starting point.

Step 3: Check After 2 Hours

Carefully open the freezer and gently touch one bottle. If it feels slushy or frozen, you've gone too long. If it's still liquid, you're in business. Close the freezer and give it another 15–30 minutes if needed.

Pro tip: The goal is water that's ice-cold to the touch but still completely liquid. Think of it as water on the edge of freezing.

Step 4: Set Up Your Trigger

Place an ice cube in a shallow bowl or tray on your countertop. This will be your nucleation site.

Step 5: Remove the Bottle (Gently!)

Open the freezer and slowly, carefully lift out one bottle. Don't shake it, bump it, or jostle it. Even a small disturbance can trigger freezing before you're ready.

Step 6: Pour Over the Ice Cube

Hold the bottle a few inches above the ice cube and start pouring. Watch closely, you should see ice crystals forming instantly as the supercooled water hits the frozen surface. The ice spreads through the stream and up into the bottle in a mesmerizing cascade.

Adult help recommended: Younger kids might need help with the pour to avoid spills or accidental bumps.

What to Expect (and Troubleshooting)

Instant ice can be finicky. Here's what might happen and how to adjust:

It Worked!

If you see ice forming the moment the water touches the cube, congratulations! You've successfully supercooled your water. Try it again with another bottle, or experiment by tapping the side of a bottle instead of pouring.

The Water Froze in the Freezer

This means the water got too cold or sat too long. Ice crystals formed inside the bottle before you could trigger nucleation yourself. Next time, reduce the freezer time by 15–30 minutes.

Nothing Happened

If the water pours normally and doesn't freeze, it wasn't cold enough. Try leaving it in the freezer for another 15–30 minutes. You can also try using a colder freezer setting or switching to smaller bottles, which chill faster.

The Bottle Froze When I Picked It Up

Even gently lifting a supercooled bottle can cause nucleation. This is actually a fun variation, watch the ice crystals spread from the bottom to the top as you hold it. Next time, try the "tap method" instead of pouring: gently tap the side of the bottle with your finger and watch it freeze from the inside.

Real Talk: Why This Experiment Can Be Tricky

Unlike some experiments where the results are predictable every time, instant ice depends on a lot of variables, bottle size, freezer temperature, how pure your water is, and even how gently you handle the bottle. Some days it works perfectly. Other days, not so much.

That's okay. Science experiments don't always go as planned, and troubleshooting is part of the learning process. If it doesn't work the first time, adjust one variable and try again. Each attempt teaches you something about the conditions needed for supercooling.

Variations to Try

Once you've mastered the basic instant ice experiment, here are a few twists:

- Ice Spike Formation: If your bottle freezes in the freezer instead of staying supercooled, check for ice spikes, thin towers of ice that sometimes form on top. These happen when water expands as it freezes and pushes through a small opening.

- Tap Instead of Pour: Try tapping the side of a supercooled bottle with your finger and watch the crystals spread from the point of impact.

- Slushy Challenge: Pour supercooled water into a bowl and stir it rapidly with a spoon to create instant slushy ice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I use tap water instead of purified water?

Tap water contains minerals and particles that act as nucleation sites, so it tends to freeze at 32°F like normal. Purified or distilled water gives you the best chance of supercooling.

Q: How cold does the water need to be?

Supercooled water is typically between 20°F and 30°F, below freezing but still liquid. Every freezer is different, so you'll need to experiment with timing.

Q: What if my freezer doesn't get cold enough?

Some freezers run warmer than others. Try placing the bottles near the back or bottom, where it's usually coldest. You can also use smaller bottles, which chill faster.

Q: Is it safe to drink supercooled water?

Yes, supercooled water is just regular water that hasn't frozen yet. Once it warms up a bit, it's perfectly safe to drink.

Q: Can I do this experiment in winter outside?

Potentially, if outdoor temperatures are consistently below freezing and you have a sheltered spot. However, controlling the exact temperature is harder outdoors, and the bottles might freeze solid before you get to them.

Disclaimer

This experiment involves very cold water and glass or plastic bottles. Adult supervision is recommended, especially when handling items from the freezer and pouring liquids. Work over a tray or sink to catch spills. If using glass bottles, handle them gently to avoid breakage. This activity is intended for educational purposes and should be conducted with care. Results may vary depending on freezer temperature, water purity, and bottle type. Tierney Family Farms is not responsible for any messes, injuries, or outcomes resulting from this experiment. Always prioritize safety and follow proper handling procedures.

Supercooling and nucleation might sound like complicated science terms, but they explain one of the coolest (literally) tricks water can pull off. Whether your instant ice works perfectly the first time or takes a few tries, you're learning about the hidden conditions that control freezing: and that's pretty powerful knowledge. Happy experimenting!