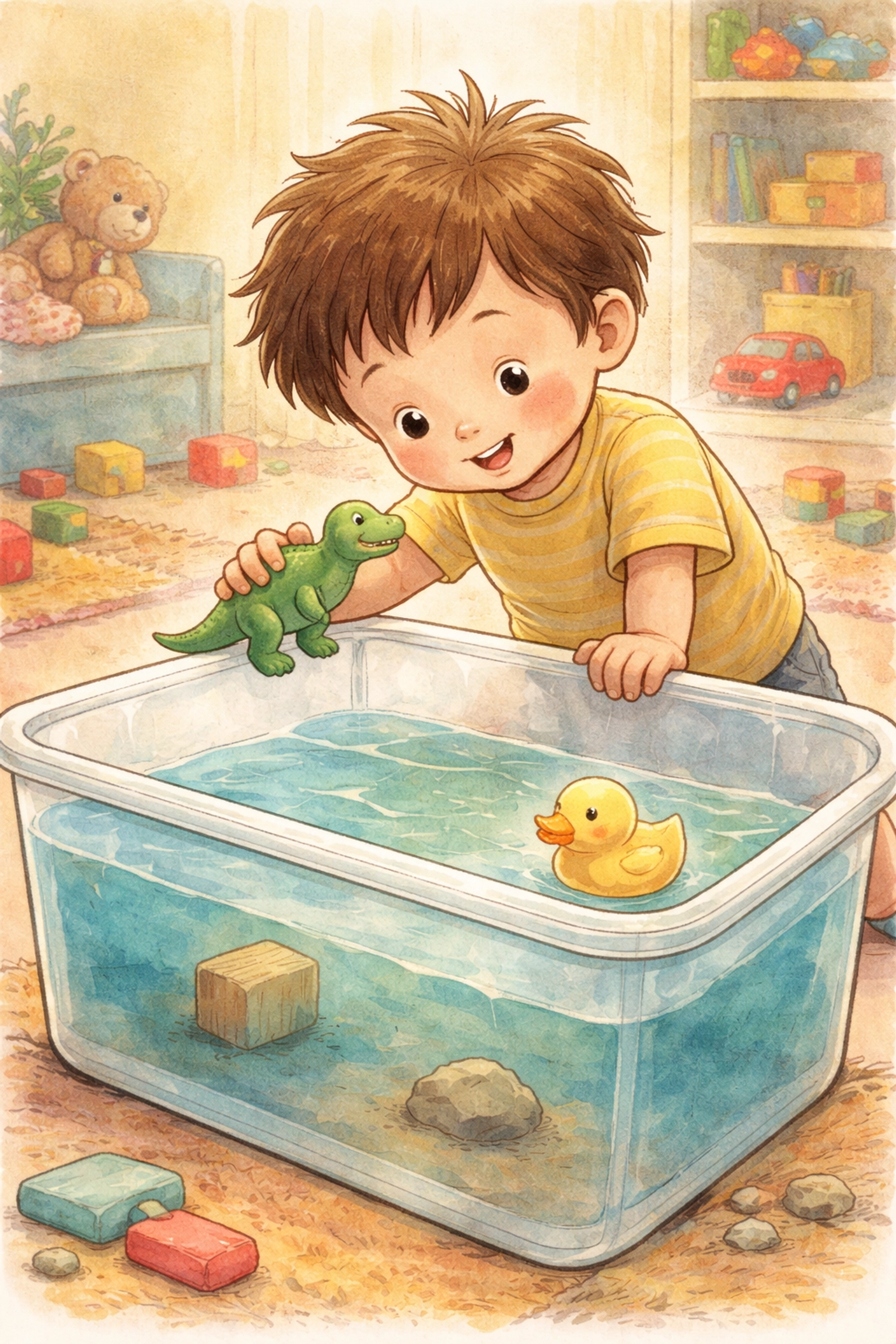

Yes, a sink or float experiment can be a wonderful activity for toddlers. It's one of the simpler science activities you can set up at home, and it tends to hold kids' attention because the results are immediate, drop something in, and you see what happens right away. For curious little ones who are figuring out how the world works, that instant feedback can be pretty satisfying.

This activity works well for children as young as two (with supervision, of course) and remains engaging for kids up to around age seven. The skill level fits best for ages three to five, but younger toddlers can participate with a bit of help, and older siblings often enjoy joining in too.

Quick Project Overview

| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Skill Age Range | 3–5 years |

| Enjoyment Age Range | 2–7 years |

| Setup Time | 10–15 minutes |

| Play Time | Unlimited (many kids stay engaged for 20–45 minutes) |

| Budget | $0 if using household items |

What You'll Need

The beauty of this experiment is that you likely have everything on hand already. Here's a simple materials list with estimated costs if you needed to purchase items new:

| Material | Likely Have at Home? | Estimated Cost (If Purchasing) |

|---|---|---|

| Large plastic bin, tub, or sink | Yes | $5–$10 |

| Water | Yes | $0 |

| Towels (for cleanup) | Yes | $0 |

| Small toys (rubber duck, plastic animals, toy cars) | Yes | $0–$5 |

| Kitchen items (wooden spoon, metal spoon, plastic cup) | Yes | $0 |

| Natural items (rocks, leaves, sticks, pinecones) | Yes | $0 |

| Fruits or vegetables (apple, orange, grape, carrot) | Possibly | $0–$3 |

| Sponge | Yes | $0–$1 |

| Cork or wine cork | Possibly | $0–$2 |

| Small ball (ping pong, foam, or bouncy ball) | Possibly | $0–$2 |

| Optional: Food coloring | Possibly | $0–$3 |

Total estimated budget: $0 using items around the house, or up to roughly $15–$25 if you had to purchase everything new (which would be unusual).

Step-by-Step Instructions

Step 1: Choose Your Water Container

Find a container large enough to hold several inches of water. A plastic storage bin works great because it gives kids room to experiment. A kitchen sink or bathtub also works fine, just expect some splashing.

Fill your container with about 4–6 inches of lukewarm water. You don't need it very deep, and shallower water tends to be easier for little hands to work with.

Step 2: Gather Your Test Objects

Walk around your home with your child and collect items to test. This scavenger hunt portion can be part of the fun. Look for things that vary in size, weight, and material. Some ideas:

- From the kitchen: Wooden spoon, metal spoon, plastic lid, cork, sponge, orange, apple, grape

- From the toy bin: Rubber duck, plastic dinosaur, small toy car, foam ball, marble

- From outside: Small rock, leaf, twig, pinecone (if dry)

- Random household items: Coin, crayon, bottle cap, paperclip

Aim for a mix of items you suspect will sink and items you suspect will float. Around 10–15 objects tends to be a good number, but there's no wrong amount.

Step 3: Make Predictions

Before testing anything, ask your child what they think will happen. "Do you think this rock will sink or float?" You might be surprised by their answers, and sometimes they'll surprise themselves.

For kids who are interested, you can create a simple chart with two columns (one for "sink" and one for "float") and have them point to or mark their prediction before each test. This isn't necessary, but some kids enjoy the structure.

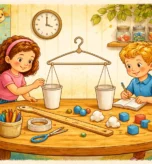

Step 4: Test and Observe

Let your child drop each item into the water one at a time. Give them a moment to watch what happens. Does it sink right away? Does it float on top? Does it hover somewhere in the middle?

Encourage them to describe what they see. If they predicted correctly, celebrate that. If they didn't, that's just as exciting, now they've learned something new about how that object behaves in water.

Step 5: Sort the Results

After testing several items, you can sort them into two piles: things that sank and things that floated. This helps reinforce the concepts and gives kids a visual sense of which types of objects tend to behave which way.

You might notice patterns together: "Hey, a lot of the metal things sank. And the wooden things floated!" This is early scientific thinking in action, even if you don't use fancy vocabulary.

Step 6: Keep Exploring (Optional Extensions)

If your child is still engaged, here are some ways to extend the activity:

- Try the same object in different positions. Does a spoon float if you lay it flat versus standing it up?

- Combine objects. What happens if you put a rock on top of a floating sponge?

- Add food coloring to the water. This doesn't change the science, but colored water can make the activity feel fresh and exciting.

- Test items when wet versus dry. A dry sponge floats, but what about a soaked one?

Why This Activity Works Well for Young Kids

It Supports Early Scientific Thinking

When toddlers guess whether something will sink or float, they're forming a hypothesis. When they drop the item in, they're running an experiment. When they see the result, they're observing and (often) revising their understanding. That's the scientific method, simplified to a level that makes sense for a two, three, or four-year-old.

It Builds Vocabulary

This experiment creates natural opportunities to introduce words like "float," "sink," "heavy," "light," "buoyant," and "dense." You don't need to drill these: just use them casually while you play. "Look, the cork is floating! It must be buoyant."

It Develops Fine Motor Skills

Picking up small objects, carrying them to the tub, and dropping them into water all require hand-eye coordination and grip strength. For toddlers still developing these skills, this kind of activity provides good practice without feeling like work.

It Encourages Focus and Independence

Many children will stay with this activity for longer than you'd expect. The immediate feedback: sink or float, right before their eyes: keeps them engaged. And because the rules are simple, kids can often continue experimenting on their own once they understand the setup.

Tips for Success

Expect water on the floor. Lay down towels before you start, and dress your child in clothes you don't mind getting wet. Some families do this activity during bath time to contain the mess.

Let them lead. Resist the urge to correct predictions before testing. The learning happens when they see the result themselves.

Keep sessions short if needed. Some toddlers will happily play for 45 minutes; others lose interest after 10. Both are fine. You can always come back to it another day with new objects.

Supervise closely. Any activity with water and young children requires your attention. Small objects can also be a choking hazard for kids who still put things in their mouths.

Wrapping Up

A sink or float experiment is about as simple as science activities get, but that's part of what makes it so useful for young children. It requires minimal prep, costs nothing if you use what's already around your house, and can be repeated with different objects over and over again.

Your toddler may not fully understand the physics of buoyancy and density: but they're building the foundation for that understanding, one dropped rubber duck at a time.

If you're looking for more hands-on projects to try with your kids, check out our guide on how to create a DIY worm composting bin with children or explore making a kitchen scrap regrow garden for under $10.

FAQ

- What are the best items to test for sink or float? Everyday household objects like spoons, plastic toys, corks, coins, and fruit are perfect. Try a mix of heavy and light items to see what surprises the kids!

- How can I make the experiment more challenging for older kids? Ask them to predict what will happen before they drop each item in. You can also try adding salt to the water to see if it changes whether an item sinks or floats.

- Is this a messy activity? It can be a little splashy! It's best to do this in the kitchen, a bathroom, or even outside. Placing a towel under your water container will help catch any stray drips.

References

- Research on early childhood development and hands-on learning

- Studies on vocabulary acquisition through sensory play

- Child development literature on fine motor skill development

- Educational resources on introducing scientific method to young children